“It’s Not the Plant:” Scientists Blame Sand, Seaweed for KB Beach Woes

Annali HaywardJanuary 31, 2020

Preliminary conclusions shared at Tuesday’s Village Council meeting reassured local leaders that a nearby sewage plant is not the sole cause of beach bacteria. But as another summer of sargassum lies in wait, there’s no let-up in the pressure to solve one of the island’s most intractable problems.

Scientists from the University of Miami presented preliminary results of their beach bacteria study to the Key Biscayne Village Council Tuesday night, all but clearing a long-suspected culprit of the island’s water woes: the Central Wastewater Treatment Plant.

“It’s not the plant,” said researcher Peter Sahwell, whose statistical and physical modelling found “no environmentally meaningful correlation” between bacterial concentrations at the plant and the beach.

“It is not a significant source of contamination when operating as designed,” Sahwell’s presentation read.

The plant, owned and operated by Miami-Dade County Water and Sewer Department, is undergoing “substantial reconstruction,” according to WASD county director Douglas Yoder, as part of a consent decree handed down for violations to the EPA Clean Water act before 2012.

The site on Virginia Key releases treated wastewater 8.5km away from Key Biscayne’s beach via its ocean outfall pipeline.

Sahwell studied 27 years of data — in particular, the concentration of fecal coliform at the outfall versus enterococci at the beach — and found that an unheard-of level of 800,000 colony-forming units (CFU, per 100ml of water) would be needed at the outfall to trigger a public advisory.

“That’s just not on the records,” he said.

So if it’s not the plant, what is it?

Sahwell’s colleague Afeefa Abdool-Ghany said Tuesday the source of the bacteria appears to be the sand and the seaweed itself.

Sand and seaweed: how did the research work?

With study leader Professor Helena Solo-Gabriele, Abdool-Ghany explained Tuesday how their yearlong study (funded by the Village for $50,000) works. The team split the beach into several zones, from the ‘supratidal’ — above the high water line — all the way through to ankle, knee and finally waist-deep water, where the Florida Department of Health take their weekly samples.

In each zone researchers sampled what was available: sand; seaweed; ‘integrated’ sand and seaweed (the brown mulch produced when the seaweed is raked or buried into the sand) and of course, water.

From there, analysis looks first at bacteria levels in the samples (for which the team has 11 months of data) before focussing — crucially — on their DNA sources, using a process called microbial source tracking (MST).

A gradient appears to show that initial bacteria counts decrease as you move further down the beach and out into the water. The highest bacteria levels are in the seaweed itself, followed by the integrated mulch. Water levels vary slightly but generally they are lower than the dry samples and decrease as you move from ankle to waist-depth.

Council members were surprised Tuesday to hear that two days after October’s 100,000-gallon sewage spill from the plant, bacteria levels in the water were actually “reversed,” showing far lower bacteria counts than before (11 CFU/100ml at waist-depth). Though it appears to be much lower, Solo-Gabriele did confirm that there is still bacteria in treated effluent.

Animal, vegetable or mineral?

That first part of the source analysis covers about 11 months of data, but the million-dollar question — where is it coming from — hinges on three months’ of MST data processed so far, with nine more pending.

Still, Solo-Gabriele is reasonably confident their current working hypotheses will hold.

The DNA ‘markers’ chosen included dog, gull and two types of human indicators. Dog returned negligible results and gull showed up at low levels in the intertidal and shallow water zones, “where birds like to hang out,” as Abdool-Ghany said. There is currently no marker available that could test for manatee bacteria.

That leaves human — not exactly a surprise, but the results so far are not totally conclusive.

“You can’t really pinpoint it,” said Abdool-Ghany, who described the pattern as sporadic — apart from a notable spike in the seaweed itself. A July, 2019 reading put it as high as 1,115 CFU/g of dry seaweed. That’s around fifteen times the level needed to trigger a beach closure from FDOH.

Dry seaweed, Solo-Gabriele explained, incubates the bacteria because it is decaying. When it is also buried into the sand, around the supratidal zone, it breaks down and the moisture and sun makes the temperature increase, creating “the perfect environment” for bacteria growth.

“Then you have wave action,” she continued, which washes bacteria back into the water.

So, where is it coming from?

The answer is still not clear. Council Member Ed London asked whether Key Biscayne’s remaining septic tanks could be to blame by leaking effluent into the groundwater or even the sewage system.

“Based on the data we’re seeing, I don’t think it’s the septic system,” said Solo-Gabriele, explaining that usually septic tanks cause problems for municipalities when they leak into rivers, which Key Biscayne does not have.

There are still 154 septic tanks on the island. 28 of those have been served notices by DERM that they have missed their deadline. The next zone’s deadline is Jun. 30.

What are local leaders doing about it?

Also present Tuesday was Chip Jones, president of Beach Raker, who have been contracted by the Village of Key Biscayne since at least 2014 for daily beach maintenance.

In the summers of 2018 and 2019 standard practice during peak times was to ‘bury’ excess seaweed — usually sargassum — by rolling it over into the sand. However as local leaders grew to understand the issue, hauling large amounts became the norm, though manageable amounts are still buried. Understanding of the issue has been aided in part by nonprofit watchdogs like Miami Waterkeeper, whose director Rachel Silverstein “highly recommended” the Village stop burying seaweed in the fall of 2018.

The Village Council met Jan. 14 with City Commissioner Ken Russell to discuss plans for a more permanent arrangement for hauling to a site on Virginia Key, where it could potentially be composted. An update on that project is expected in two weeks, said Village Manager Andrea Agha Tuesday.

Meanwhile Jones said that although wintertime usually means less seaweed, his team hauled 500 cubic yards within three days about two weeks ago.

That’s nothing compared with what’s coming, said Jones, whose firm manages beaches from Nassau County to the Florida Keys.

“5,000km of sargassum is floating out in the ocean right now waiting to wash up on Florida’s beaches,” he told the Council.

But wait… there’s more

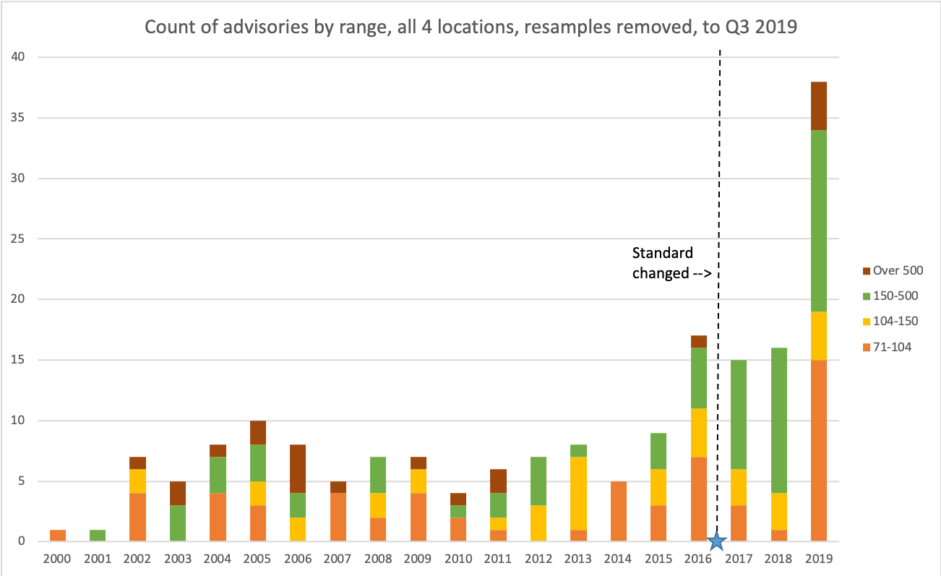

As was revealed at the Village’s water quality workshop in November, the FDOH decreased the testing standard for their weekly, waist-deep water sampling from a minimum of 104 CFU/100ml to 70 CFU/100ml in 2016.

Council member Luis Lauredo asked how this change affected the frequency of beach advisories during the workshop. At the time, Dr. Samir Elmir, DOH director of environmental health, said they were not sure of the answer. Solo-Gabriele said it would be good to see the datasets and look at whether the number of advisories has gone up.

Now, data obtained from the FDOH and analyzed by Key News (and checked by a scientist from the University of Miami) gives a wider picture.

The data goes back to 2000 and casts a wider net, covering all four locations on the island where DOH testing takes place — Crandon North and South, Key Biscayne, and Bill Baggs Cape Florida — in recognition of the fact that, as previously stated by Miami Waterkeeper, water movement varies greatly and can impact testing.

Once resampling data is removed, there was a slight decrease in the number of readings over 70 CFU/100ml (and therefore triggering an advisory) across these four locations, from 17 in 2016, to 15 and 16 in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

However in 2019, even with data for the final three months of the year unavailable, there was a marked increase to 38 advisories.

Even more telling, the number of readings falling in between the two levels of 70 and 104 CFU/100ml was 19, but the number of advisories above that was 50. Most of them (36) were in the range of 150-500 CFU/100ml and 15 of those happened in 2019.

The worst month was September and the worst-performing location was Crandon Park South with 16 readings, 6 of which were between 150-500 CFU/100ml.

A statement from the FDOH said the change in level to 70 CFU/100ml was made because epidemiological studies reviewed by the federal Environmental Protection Agency indicated that the risk of gastrointestinal illness in swimmers exposed to water with high bacterial counts was slightly higher than previously thought.

“Exposure to water with bacterial counts at or below 70 CFU would result in about 36 of 1,000 swimmers expected to become ill from water contact,” the statement continued.

In response to public records requests, WASD spokesperson Jennifer Messemer-Skold told Key News “there have been no leaks or breaks to the [underwater transmission] lines from 2018 to date. Department assets such as those, which are continuously in use, are not typically inspected. However, WASD staff monitors these assets for changes in pressure and flow that could indicate an instance where maintenance would be necessary.”

Further records requests from Key News to WASD show at least seven instances of department staff repairing leaks along Harbor Drive since October 2019, including maintenance at 153 Harbor Drive Jan. 22. A broken mains pipe outside the Tennis Center at 7200 Crandon Boulevard was also fixed Jan. 22.

So, is it safe to swim?

Gio Baracco M.D., Professor of Clinical Medicine at the Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine reviewed the data and told Key News:

“The number of samples with high bacterial counts and the number of advisories have been increasing over time, and this does not seem to be fully explained by the change in the cutoff values.”

Baracco said it is difficult to know what this means in terms of health risks.

“On one hand, the concentration of Enterococcus and coliform bacteria are surrogate markers for fecal contamination,” he said. “There are some old studies correlating it with mild gastrointestinal illness, and therefore one may conclude that waters outside Key Biscayne are getting more hazardous.”

But, said Baracco, the system does appear to be working as it should be.

“It should be noted that over 90 percent of all samples are well within acceptable ranges,” he said.

“The fact that DOH is testing, retesting, and issuing advisories when the counts are high means that the public should be reassured that this program is doing exactly what it is supposed to do, which is to monitor and alert the public, and in the absence of an advisory the waters are safe.”

A statement to Key News from the FDOH in response to the data read:

”The Florida Department of Health (DOH) will continue to monitor beaches in the Key Biscayne area as part of our coastal beach monitoring program and issue water quality advisories as needed so that the public will be aware of any potential increased health risks that may be present. These advisories will allow the public to make an informed decision about which beaches to go to.

We share all our monitoring data with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) for use in their programs. Advisory information is also shared with FDEP so that they can conduct the statutorily required follow up investigations.

At this time DOH does not have the resources or expertise to determine the source of the increased levels of bacteria we are now seeing in the area.”

This story has been updated.

Responses

Ezra

Feb 11

Incredibly informative article. Thanks for taking the time and going into detail. Excellent journalism.

The comments are closed.